Garlic Mustard

Your forest is beautiful, keep it that way.

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is a high-priority invasive species in Illinois. Large infestations of this low-growing herbaceous flowering plant limit growth and productivity of native plants and threaten the long-term health of forests limiting how we enjoy them now and in the future.

- Status: Highly invasive.

- Plants produce as many as 8,000 seeds and spreads quickly.

- Grows densely and crowds out native plants.

- Monitor forests yearly to prevent infestations.

- Management options: Hand pulling, prescribed burns, herbicide.

Download a garlic mustard infosheet

Impact

Garlic mustard’s early spring growth can quickly cover the forest understory. Infestations form a monoculture that competes with native plants for light, water, and nutrients. This threatens wildflowers, tree seedlings, insects, wildlife, and future forests. Large populations reduce nutrients in the soil and release allelopathic compounds that slow the growth of other plants.

Infestations impact the ecosystem and reduce the ability to harvest timber, hunt, collect mushrooms, enjoy spring wildflowers, watch birds, and spend quality time in beautiful, healthy forests.

History

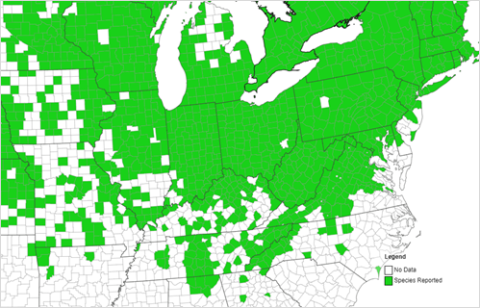

Garlic mustard is native to Europe and was first recorded in North America in 1868. This potherb was historically eaten in early spring when few greens were available. It was first reported in Illinois in 1918 and by the late 1980s was recognized as a problem species. It has been reported in at least 70 of Illinois’ 102 counties.

Regulation

Eight states have declared this invasive as a prohibited or noxious weed. Illinois does not currently mandate or regulate it.

Identification

Garlic mustard is commonly found in shaded and semi-shaded woodlands. Make it a habit to look for invasive species whenever in the woods. Monitor for garlic mustard along pathways of entry such as forest edges, creeks, trails, and in disturbed areas. Mark plant locations with a map app or flags.

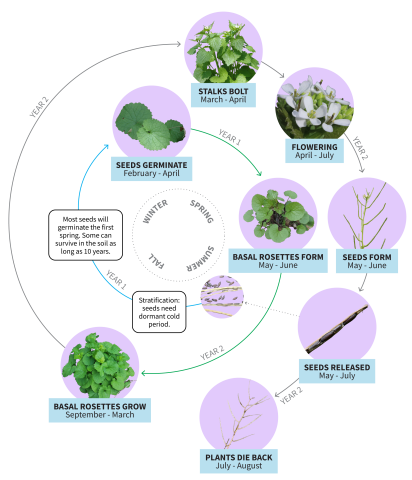

Garlic mustard has a two-year, or biennial, growth cycle. First- and second-year plants will grow together and in large infestations will rotate dominance in the landscape every other year. Garlic mustard is easiest to identify in spring when second-year plants are flowering. Explore photos of each stage of growth at the end of the page.

Year 1 Plants

Seeds require a cold dormant period, or stratification, of at least 8 months. Most seeds germinate in spring, as early as February, with some continuing through fall. Seeds can survive in the soil up to 10 years.

Plants grow into multi-stalked clusters of low-growing basal rosettes. Leaves are kidney-shaped with rounded scalloped edges that smell like garlic when crushed. The plant will overwinter as a basal rosette. First-year plants can easily be overlooked at low levels.

Year 2 Plants

In the early spring, basal rosettes will have a surge of growth as they bolt and bloom. The flowering stalk is 1- to 4-feet tall with triangular, toothed-edged leaves. Its flowers have four white petals. Seeds form in upright seed pods known as siliques.

As plants die, they dry and release an average of 360 black seeds in early summer. Large plants can produce more than 8,000 seeds. Clusters of dead dry stalks will likely have first-year germinates nearby.

| Southern Illinois | Northern Illinois | |

|---|---|---|

| Flowering | Starts early April | Starts mid-April |

| Seeds Form | May | Mid-April to June |

| Seeds Release | Late May | Starts mid-June |

Management

Removing garlic mustard is a multi-year process that focuses on preventing at least 90% of plants from producing seeds to prevent spread. Be prepared to manage annually for at least five years to deplete the seed bank and plan for long-term monitoring to prevent reinvasions. Sporadic management can make infestations worse.

No management method is entirely effective. Before treatment, develop a long-term strategy that considers available time and labor resources, as well as the infestation size and location.

Land managers face competing obligations; prioritizing sites for management is important for success. For help prioritizing sites, explore a management decision tree in the Midwest Invasive Plant Network’s Garlic Mustard Guide.

- Monitor for new or growing populations along pathways of spread and focus on treating manageable garlic mustard populations.

- Top priority sites are new invasions, satellite populations, plants near trails and streams, and the leading edge of infestations.

In Illinois, there is a 6- to 8-week window in the spring to control second-year plants before they produce seed. Do not attempt removal if plants are dry and seeds are falling out; this will further its spread.

Add a reminder to your calendar

Prevention

- Keep garlic mustard out of your forest: If visiting other properties, stay on established roads and trails and clean boots, tires, and horse hooves before returning to your property.

- Work with neighboring property owners: Discuss concerns about invasives with neighboring property owners and plan to work together to manage them.

Mechanical removal

Remove plants after they bolt and before flowering.

Hand pulling

These shallow-rooted plants are easy to pull from the soil once they bolt. Pulling is labor intensive and may only be practical for small infestations or if a lot of people are available. Grasp the stalks at the base and gently tug to remove the S-shaped root. Plants with flowers or fruit should be put in bags. Leave tied bags in the sun for several days to kill the seeds before throwing bags away.

Consider hosting a garlic mustard pull volunteer event for sites that would otherwise be damaged by herbicide or prescribed burn control. Explore resources in the How to Host a Garlic Mustard Pull Toolkit.

Mowing/Cutting

This method works for large populations of bolting plants. Cut stalks at ground level to eliminate seed production. Stalks with siliques can still form viable seed.

Prescribed fire

In forest communities adapted to fire, a prescribed burn can help control large infestations and stimulate native plant growth. Always follow state and local regulations and safety protocols. Managers need an approved plan and a permit from the Illinois EPA. Explore an Introduction to Prescribed Fire and more resources for implementing a prescribed fire.

A mid-intensity burn in the spring is most effective. A handheld propane torch can also be used for spot treatments. Fire will remove leaf litter and prompt seeds to germinate. You can treat the new seedlings with herbicide to deplete the seed bank faster.

- Early spring burns target basal rosettes and bolting plants but can harm early wildflowers.

- Late spring burns target new seedlings and basal rosettes but can damage actively growing plants.

- Fall burns can reduce basal rosettes.

Chemical control

Herbicide can be a low-cost, low-labor option for large infestations. Always read and follow product labels before use. Avoid impacting desirable plants with herbicide overspray. Apply enough herbicide to wet foliage, but not so much that it drips off.

Anyone who applies pesticide on public lands must be licensed. Learn more from the Pesticide Safety Education Program.

Use products with Glyphosate or Triclopyr to treat basal rosettes and bolting plants. Apply in early spring or fall. Late applications, during or after flowering, can reduce viable seed production but are not entirely effective.

Concentrations

- Glyphosate, 1% to 3% v/v diluted in water.

- Triclopyr, 1.5% v/v diluted in water.

Deer exclusion

White-tailed deer move seed and avoid eating garlic mustard, so infestations can increase herbivory pressure on native plants. This can reduce native plant abundance and allow garlic mustard to increase in dominance. Exclude or manage large deer populations when removing garlic mustard.

Biological control

Researchers continue to explore if European aphids that feed on garlic mustard can be used for control.

No management

Long-term monitoring has provided some evidence that long-standing garlic mustard populations, at least 50 years old, may be self limiting and could decline without management. These findings are not well supported.

Research Updates

Midwestern researchers recently explored the time frame needed to apply herbicides in order to prevent seed production.

Results: Applying Glyphosate and Triclopyr during the flowering stage reduces viable seed production. This was not 100% effective, so do not use this as a primary method to control garlic mustard. This gives land managers an extra 2 to 3 weeks to apply herbicide to garlic mustard in the spring.

References

- Residence time determines invasiveness and performance of garlic mustard in North America

- Garlic Mustard in the Midwest: an Overview for Managers

- Complex population dynamics and control of the invasive biennial Alliaria petiolata.

- Do applications of systemic herbicides when green fruit are present prevent seed production or viability of garlic mustard?

Authors: Chris Evans, Emily Steele. Updated October 2022.

Photo Gallery

_cropped horizontal.jpg)

_horizontal crop.jpg)

Photo 1: A newly germinated garlic mustard plant with kidney-shaped leaves. Photo 2: A year-one plant in its multi-stalked basal rosette form. Photo 3: A year-two plant that has bolted and flowered. Photo 4: The small flowers have four, white petals in the shape of an X. Photo 5: The curved root of a pulled plant. Photo 6: A plant that has completed flowering and is producing fruit in its seed pods. Photo 7: The small black seeds ready to fall out. Photo 8: First-year germinates growing under the dead stalks of last spring's year-two plants in the fall.